This is the final chapter to the book Sex in the Comics from 1985. Like I said before, the text is as big as possible (which is why I'm able to retype it in its entirety). The previous chapters, which I've also posted each Saturday, are probably linked to in the 'Linkwithin' blurbs at the bottom.

Here is the text by author Maurice Horn. I don't know how to feel about gay sex being implied as a perversion, though I guess if I were writing this book and had to compartmentalize different aspects of sex in the comics, and it was the 1980s, I might end up doing the same thing. Here is the last chapter of this book though.

For quite some time, but more particularly during the last two decades, the comics have been venturing far afield into the vagaries of sexual behavior, with cartoonists wading bravely into the murky waters of what are commonly called “deviations and perversions”. Many general encyclopedias still define “perverted sex” as any sexual act whose purpose is not procreation. That covers a lot of territory. It is not our intention in this chapter to catalogue each and every so-called deviation—a task better left to psychologists and sociologists—but to inquire as to the images, both positive and negative, that the comics have projected out of, and onto, this area of human behavior.

Of all the sexual minorities that deviate from the “straight” model of heterosexuality, homosexuals are, by sheer weight of numbers, the most visible. In an article in In Touch, Jerry Mills asserts, “Until recently, gay characters hardly ever appeared” in the comics. That assessment isn't strictly accurate. Homosexuals of both genders did appear in the comic pages as early as the twenties, although they were never characterized explicitly. If they were men, they were usually characterized as fussy and mincing, like the type who kept disrupting the trysts of Rosie and her beau, to the annoyance of both, or the openly “swishy” character who almost openly propositioned Moon Mullins with an offer of a job as a bodyguard, only to be given short shrift by the outraged Moon. Other blatantly effeminate characters also cropped up from time to time in such strips as Secret Agent X-9, Mandrake, and Dick Tracy (a pronounced lisp and gestures were among the telltale signs).

These were, however, only fleeting creations. Terry and the Pirates, on the other hand, featured supporting characters who exhibited unmistakable supporting characters who exhibited unmistakably homosexual (or ambiguously bisexual) proclivities. The corpulent, effeminate, Papa Pyson was a brigand chief who liked to be wheeled around his mobile chair by a muscular “aide de camp” and was tended to in his sybaritic pursuits by young limp-wristed minions. He strictly forbade his troops to have any intercourse with the corps of female prostitutes the Dragon Lady was keeping nearby as auxiliaries, and cringed and cringed at the very thought of close physical contact with a woman. An even more straightforward example was provided by Sanjak, a mysterious Double agent who turned out to be a woman by the name of Madame Sud, with more than professional designs on Terry's heartthrob April Kane. (That adventure took place in 1939 in what was then known as French Indochina—perhaps the first example of American involvement in Vietnam.) Later during the course of the war, Sanjak turned up again as Captain Midi, a dashing French air force captain but actually a spy for the Japanese in drag, and again her interest in April proved her undoing—a clear if double perverse case of cherchez la femme.

In the long history of the comics George Herriman stands apart in his mischievous delineation of Krazy Kat as a creature of indeterminate gender (Krazy Kat once described him/herself as both a bachelor and a spinster—wryly adding that this situation would last “until I get wedded”). Krazy Kat notwithstanding, it has been a slow march to toleration, if not acceptance, From Carl Barks' homophobic remarks in Donald Duck, where a sissified character asks museum guard Donald for “the lace and tatting collection” to Garry Trudeau's matter-of-fact understanding in Doonesbury, in which Joanie Caucus discovers that her old flame Andy is gay. In between came tales of sex change (in Weird Science and Camelot 3000) and attempted homosexual rape (in The Incredible Hulk) and even a story about the reunion of Captain America with his long-lost boyhood pal who grew up to become gay (Cap, of course, grew up to become a superhero, but that's another story). Finally, let's not forget S. Clay Wilson's notorious (and hilarious) Ruby the Dyke.

Until recently homosexuals in the comics were secondary or satirized characters. However, with the growth of the gay liberation movement and the proliferation of publications since the seventies, overtly homosexual characters have become full-fledged protagonists, often in their own comic features. Unfortunately more often than not these features are afflicted with a pornographic outlook that would make the readers of Hustler blush: the wealth of genitals on display is matched only by the poverty of the storyline. Even the strips that are more stylistically restrained are just as raunchy thematically, with an overabundance of salacious lines and off-color jokes. A character in Castro, for instance (the strip is named for the gay district of San Francisco, not the jolly Fidel of Cuba), exclaims after a visual inspection of his friends backside, “Honey, if I dropped dead now, I'd want to come right back as yer bicycle seat, an' roll around in heaven all day.”

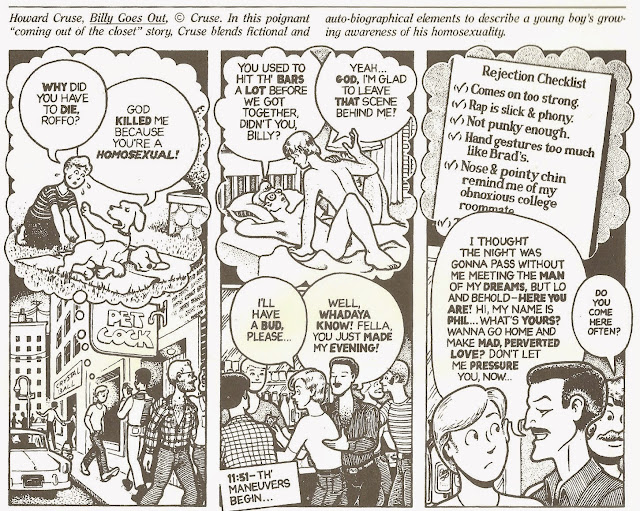

The homosexual audience is apparently large enough to support at least one gay underground comic book. Gay Heart Throbs made its bow in the mid-seventies, lasted a few issues and was superseded by Gay Comix in 1980. Howard Cruse, an established cartoonist with Playboy, the National Lampoon and other publications, is the editor, and he has been able to attract a good number of talented cartoonists to his magazine, Rand Holmes and Burton Clarke have drawn covers, and his regular contributors include Robert Triptow (whose one-pager, Castroids, is also about the Castro district) and Dutch cartoonist Theo Bogart. The distaff side is well represented by Lee Marrs, who specializes in tales of tongue-in-cheek domination, Roberta Gregory, the editor of the first lesbian comic, Dynamite Damsels, and Mary Wings, former editor of the self-explanatory Dyke Shorts. The best thing about the magazine, however, is Cruse himself: his autobiographical Billy Goes Out is a quite poignant “coming out of the closet” story.

There have been a number of great stories about homosexual love (many of them by straight cartoonists) in Europe, notably in France and Holland, but no gay comic book has yet appeared there. Not so in Japan, where a magazine called Juné specializes in homosexual stories (mostly drawn by women artists!) and enjoys tremendous popular success with teenage readers of both sexes. In his excellent study of Japanese comics, Manga! Manga!, Frederick Schodt describes a typical issue of the 150-page magazine: “pin-up color photographs of androgynous foreign rock stars and scantily clad teenage boys, with poems; eleven comic stories and short strips about young gay men; a short, illustrated prose story of gay interracial love in prewar Japan” along with “drawings by readers of young boys embracing; reviews of amateur comic magazines devoted to the 'beautiful boy'; confessions of gay love, purportedly written by readers”, etc.

If homosexuality has been the most prevalent sexual deviation in real life, sadomasochism has been the most frequently depicted sexual perversion in the comics. As a matter of fact, in the forties and the fifties, there was an entire category of comic books that specialized in picturing women in provocative and often submissive poses for the delectation of adolescent male readers. The drawings, especially those on the covers, constituted the main attraction, with plot and characterization most often very skimpy indeed—a fact that did not unduly disturb aficionados of the genre (who, after they grew up, took to referring to that brand of illustration as “good girl art”, a term that has angered feminists to no end). The trend even spilled over into mainstream comics of the time, with newspaper strips like Steve Canyon, Rip Kirby, and Dick Tracy occasionally delving into sadism and bondage.

There were quite a few publishers of sadomasochistic comics, but Fox Publications and ME Comics were generally acknowledged as leaders of the form. In title after gaudy title (Phantom Lady,Cave Girl, Jungle Lil, Thunda, etc.) they offered women in all kinds of deranged positions—bound and gagged, tied to racks, threatened with whips and branding irons, molested by freaks and degenerates—all drawn in exquisite detail by such masters as Bob Powell, Matt Baker, and Frank Frazetta. These beauties never failed to display an over-abundance of charms; in fact, the artists pushed breast fetishism to such ludicrous extremes that it had an undesirable side effect of attracting the special ire of Dr. Wertham. “One of the stock mental aphrodisiacs is to draw girls' breasts in such a way that they are sexually exciting”, he fulminated in Seduction of the Innocent. “Whenever possible they protrude and obtrude”.

After the Comics Code came into effect, the theme of breast fetishism and bondage found their outlet in scores of semiunderground publications catering to an impressively large clientele. In these unbridled tales of illustrated erotic fantasy all the women were big-busted and scantily clad, or else they went around in leather outfits and highly-laced boots. They generally operated in a world devoid of men (an intriguing psychological quirk), with the “bad girls” (usually older) submitting the “good girls” to a fiendish array of ordeals, degradations, and tortures. No overtly sexual act was ever performed, a fact that inclined the authorities towards indulgence, and the genre accordingly flourished into the sixties,when the appearance of more sexually explicit comic stories soon took away from their raison d'être. Most of these publications were artistically god-awful and nauseating in their repetitiveness, but two achieve cult status due to their better-than-average storylines and outstanding artwork. One, Sweet Gwendoline, is the tale of a nubile innocent victimized by a succession of sadistic females, drawn first by John Scott Coutts (under the pseudonym John Willie), and later Eric Stanton; the other Princess Elaine, by Eneg (Gene Bilbrew), depicts the erotic adventures of a cruel blonde dominatrix.

The most fertile ground for sadomasochistic comics proved to be Europe, where the genre found its maestro assoluto in the person of Guido Crepax. Working almost exclusively in black and white, Crepax is best known for the beautiful loving depiction of young women victimized in the course of disturbing sadomasochistic adventures. La Casa Matta(“The Mad House”, later reworked as Bianca), in which a nubile schoolgirl daydreams and fantasizes her way into a cruel, erotic universe where her schoolmates, teachers and relatives become her lovers and/or tormentors, in classic Crepax fare. So is Anita, an alarming tale of sexual obsession eventually leading to self-immolation.

These predilections made Crepax the perfect choice as illustrator of two of the most celebrated models of modern erotic literature, Pauline Réage's Story of O and Emmanuelle Arsan's Emmanuelle. It should be noted that Crepax's treatment is much more faithful to the originals than their watered-down screen adaptations, Story of O in particular—described by novelist André Pieyre de Mandiargues as “the tragic flowering of a woman in the abdication of her freedom, in willful slavery, in humiliation, in the prostitution imposed upon her by her masters, in torture, and even the death which, after she has suffered every other ignominy, she requests and they agree to”—found in Crepax its ideal interpreter.

After these two resounding successes it was probably inevitable that the artist would go on to illustrate the works of the man who gave sadism its name, the Marquis de Sade himself. Crepax's Justine, based on Sade's quintessential novel of innocent womanhood tormented, abused and debased, is somewhat of a disappointment, however. This may be due to the fact that the phantasms conjured by the “divine marquis” are in the last analysis too abstract, too cerebral to be adequately expressed in graphic terms; conversely, it may be because the philosophical outpourings of the author, whose prose was respectfully preserved, tend to overshadow the artist's illustrations.

Crepax's Valentina also veers away from the straight storytelling towards straight fantasy making, half oneiric and half hallucinatory, with an overpoweringly sadomasochistic current. In the course of her wanderings Valentina travels through space and time in a universe untrammeled by rules or rationality, where she meets in turn rampaging Mongols, brutal concentration camp guards, libidinous space aliens, vicious Amazon queens and every imaginable figure of fact and legend (Bluebeard and Archimedes, Lenin and Morgan le Fey, among others). Against a splendid baroque background reeking of sensuality and decadence, Valentina is usually the victim of the most barbarous treatments: raped, whipped, quartered, impaled and branded, she always emerges Phoenix-like from her ordeals, unmarked and apparently untouched.

Of all the villains, male and female, human and animal, who constantly plague the heroine, none is so prominent or colorful as Baba Yaga, inspired by a legendary witch in Russian folklore. As depicted by Crepax, Baba Yaga is a desiccated lesbian crone who favors turn-of-the-century fashions and tries to lure Valentina away from her lover. She dons various guises to this end and in particular replays the role of the bad witch in updated versions of fairy tales such as Snow White and Hansel and Gretel. In these allegories Crepax seems to be telling us that sadomasochistic fantasy is the modern equivalent of the fairy tales of old.

Crepax notwishstanding, it tis perhaps fitting that the most outré of all sadomasochistic comic heroes should have been conceived by a Frenchman. With Marie-Gabrielle de Sainte-Eutrope, George Pichard crowned his already notorious career py pulling out all the stops in a horrendous tale of a buxom,dark-haired beauty subjected to every conceivable form of torture and torment—in full color and minute detail. Perhaps a takeoff on one of Sade's most famous anthology pieces—wherein Justine and her companions are victimized by an order of monks—Pichard has Marie-Gabrielle and her cellmates tormented by nuns who kept piously reciting the catalogue of tortures visited upon by Christian saints and martyrs, while meting out the most barbarous treatment to their helpless charges. The author then produced a sequel, Marie-Gabrielle en Orient, in which he set out to demonstrate that when it comes to torture inflicted on women, all men are brothers under the skin.

Not surprisingly, comics depicting the sexual fantasies of women are relatively rare in this male-dominated medium. There are exceptions, however, French cartoonist Marcelé has authored a number of comics showing strong, beautiful and cruel women bringing cowering, flabby middle-aged men to heel. In the United States, in 1972, Chin Lyvely and Joyce Farmer started an all-woman comic with the provocative title Tits and Clits. “It was a great success,” the co-founders later mused, “either because the subject matter was unusual and (some say) revolting, or because many people were willing to pay 50 cents for a magazine with the title of Tits and Clits.”

The focus of Tits and Clits was on female sexuality, as, to a certain degree, was that of Wimmen's Comics, which also appeared in 1972. Their subject matter, however, proved tame in comparison with that of Wet Satin, which openly proclaimed itself to be about “women's erotic fantasies,” many of which turned the table on male sexual ethos with a vengeance.

In recent years the motto of the comics might well have been “Anything goes” as far as erotic expression is concerned, with some themes seemingly straight out of Krafft-Ebbing's Psychopathia Sexualis. In fact, cartoonists have proved themselves so thorough in the graphic depiction of every quirk and singularity of human sexual behavior that an enterprising publisher has come out with an Encyclopedia of Sex entirely illustrated with examples culled from comic strips. It would be impossible to go through a checklist of every perversion known to man and see how it found its illustration in the comics, but let us note that whole stories have been built around themes of transvestism (Nazario's Anarcoma, which takes place on the outer fringes of post-Franco Barcelona), pedophilia (Dick Matena's Alice, a less than innocent reinterpretation of Lewis Carroll's tale), incest, (Enric de Sió's sensual Cuestion de Fé, the allegorical Age of Cohabitation by Dôsei Jidai) and necrophilia (Richard Corben's Lame Lem's Love).

Since comics to a certain extent are still beholden to the “funny animal” tradition, the sight of such creatures as Howard the Duck, Cerebus the Aardvark, or the White Ape commingling freely with women is hardly noticed in the context of perversion. Robert Crumb provided an ironic twist on the theme in Whiteman, wherein the protagonist forsook his nagging wife and his middle-class life to pursue his hairy lover, the animallike Yeti, into the wilds. But Whiteman can also be placed squarely—if that's the word—in the great comic strip tradition of A. Mutt, Jiggs, Barney Google and other harassed husbands (see chapter 1). From Mutt and Jeff to Crumb and back, the subject has literally come full circle.

University of Austin: The anti-woke University circles the drain

-

The University of Austin (UATX), not to be confused with the University of

Texas at Austin, was founded in October, 2021 as a sort of heterodox

university,...

28 minutes ago

No comments:

Post a Comment