Here's a book I've had since childhood. Sex in the Comics was published in 1985 and written by Maurice Horn, author of many books about the history of comics. Often when I post excerpts from books like this I include just the pictures, but the text in this is so sparse I might as well include it as well. It's in big type and the illustrations take up most of the space. The margins are wide too, which makes me think of when you were in school and had to write a report and since there was a minimum page requirement you make as much blank space as you can. The book was obviously written only to sell based on the theme of sex, which I don't think worked as well as they thought it would since I got this remaindered.

And don't worry about my cutting off prematurely like I did with Comic Art in America That was a library book I had to return before I had the chance to scan everything. This book I own.

And here is the text from the book:

There is more to sex than sex. Sex is with us, all around us, and cannot be ignored, no matter how strong the forces of censorship. Since it operates at both conscious and unconscious levels, its manifestations are always unpredictable, and its expressions unavoidable, even by prudes. Sigmund Freud devoted his lifetime to study of the sex urge (which he called “libido” —it sounds more fashionable that way) in all its incarnations, and in 1909 he came to these shores to preach the new gospel to the natives. His teachings have since born ample fruit, as thousands of his American disciples who derive a (lucrative) livelihood from his theories can readily attest.

The turn of the century today is viewed through the eyes of nostalgia as an age of sexual innocence, Freud notwithstanding. If such had been the case, however, America would be as underpopulated a continent in this good year of 1985 as when the Pilgrims found it. While art and literature (the only forms of expression ever studied by sobersided scholars and academics) only skirted the issue of sex, the more rigorous forms of American vaudeville and burlesque in openly raucous blackouts and bawdy routines. Then as now there were plenty of critics ready to indict the age for its immorality, among them the redoubtable Carrie Nation, who fulminated, “The times are lewd, besotted, and licentious!” Despite the outcries of the righteous, the show went on pretty much as before. The American newspapers greatly added to the tenor of the times, as Ms. Nation saw them, with their sensational headlines and libelous reporting, not to mention their latest attraction, the gaudily colorful comics section.

In Europe, by contrast, comics were almost exclusively designed for kids, and they accordingly addressed themselves to childish concerns—at least until the sixties, when European cartoonists struck back with a vengeance. On this side of the Atlantic, too, the explicit depiction of sexual situations was a product of the sexual revolution of the sixties. But while the subject has come into the open only in recent times, sex in the comics was not born yesterday, as we shall see.

The thread was in fact already apparent in the earliest comics, from Buster Brown, who displayed the manner of boy-of-the-world with all the girls he met, to Happy Hooligan, who turned out to be a fool at everything except the pursuit of the fair Suzanne, whom he wooed under the very nose of her disapproving father. With the establishment of the daily strip, whose public was overwhelmingly adult (in contrast to the Sunday pages, which were read by a great number of children), a somewhat more roguish version of the relationship between man and woman began to assert itself. Clare Briggs' scheming A. Piker Clerk and Bud Fisher's hustling Mutt (of Mutt and Jeff) were both inveterate horseplayers, but they both kept an eye on the ladies between races and even managed to score a few wins in that field when their occasional winnings from the ponies permitted.

H.A. McGill's The Hall Room Boys came closer to the heart of the matter. His titular heroes, Percy and Ferdy, two social climbers as inept as they were deluded, had one eye solidly fixed on the fast buck, and the other just as determinedly riveted on any skirt in sight. Whether they dated the fairest flower in the boardinghouse on the sly to spite a rival or cottoned up to a superior's homely daughter in order to win the father's favor, it was never a labor of love for these two. No sentiment there, only a yearning for the elements of social life: cold cash and warm flesh. It is therefore no wonder that the double entendres in this strip were more blatant than in any other of the earlier comic features.

The early cartoonists enjoyed greater latitude than when they were dealing with other than recognizably human characters. With Mr. Skygack, from Mars, A. D. Condo (yes, that was his real name) presented a denizen of the red planet who had come to Earth, and specifically to the good old USA, to observe (and satirize) local customs, somewhat after the fashion of the thinly veiled social and political fictions so favored by the eighteenth-century novelists (not the first or last instance of a comic-strip author revealing some hoary literary device). Skygack regularly appeared equally nonplussed by the humans' pursuit of the opposite sex, both rituals striking him, not unreasonably, as an excessive expenditure of energy compared to the results usually achieved.

James Swinnerton, one of the founding fathers of the comics, achieved much of the same distancing effect with Mr. Jack, a black-striped feline who unlike Skygack, was not content with the role of mere observer but was the protagonist of the action. A cocky cat-about-town, he was primarily attracted to showgirls (showkittens?) but, failing that, would chase after any female in sight, to the chagrin of his long-suffering wife. No trick was to low, no lie too shabby for Mr. Jack in his unrelenting pursuit of the other sex. His shenanigans became so outrageous that W.R. Hearst himself had the Mr. Jack feature yanked from the sanitized environment of his Sunday supplement, where the children could see it, and exiled to the more mature atmosphere of the daily sports pages.

Even more revealing was The Dream(s) of a Rarebit Fiend, Winsor McCay's exploration of the uncharted world of dreams. Many of the nightmares induced by the protagonists' inordinate ingestion of Welsh rarebits had Freudian overtones and exposed the roots of some of man's most universal fears—of death, of impotence, of sexual inadequacy, of social shame. In one episode a man dreams he has moved to the state of Utah and married a dozen maidens; his bliss is short-lived, however, as his wives all gang up on him to relieve him of his paycheck, In another sequence a rich old man, married to a much younger woman, longs to go back to his salad days; in his sleep he witnesses his wish fulfillment turn into a nightmare as he ineluctably slips back into infancy and is only able to greet his startled wife with baby whimperings and mumblings.

Other segments had spinsters dreaming they were pursued by hordes of panting males or eligible bachelors fighting over their favors. Some dreams were explicitly sexual, with male and female protagonists performing strange rituals in bed or carrying on ambiguous conversations while stark naked in bed. At a time—the first decade of this century—when Victorian morals and values still held sway in this country, these were bold and revolutionary statements (let's not forget that Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams was still banned in many parts of the United States during that period.

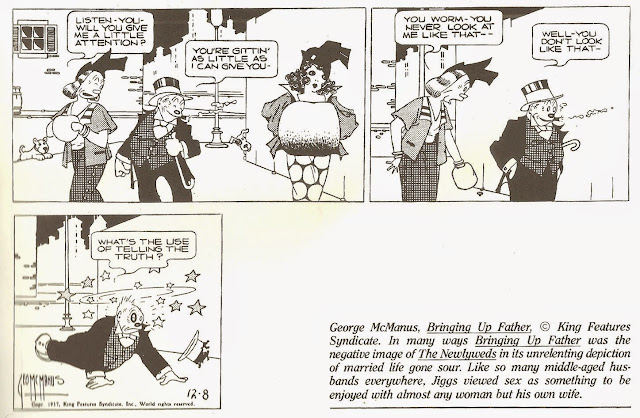

Writing in Cartoon Cavalcade in 1943, Thomas Craven averred that while the battle of the sexes had been depicted with unprecedented ferocity in the comics pages, “the charms of sex have never Found their way into American cartooning.” His statement may have been accurate as far as the great majority of cartoonists were concerned, but it could never have applied to the irrepressible George McManus, whose creations conveyed a joyous, even ebullient view of sex. At he same time, he was responsible for the most ferocious battle of the sexes in the history of the comics, that of Jiggs and Maggie in Bringing Up Father. McManus started writing and drawing in praise of sex as early as 1904 with The Newlyweds, where the theme appeared under the respectable cloak of connubial bliss. It was further defined in Rosie's Beau, wherein Rosie and her “beau” carried on the most outrageous cooing and petting at every opportunity, in blissful oblivion of fire, flood, burglary or whatever catastrophe was currently taking place around them.

As for Jiggs and Maggie, they are best known for their earthshaking fights, usually triggered by Jiggs trying to sneak out of the house to join his cronies for a friendly game of pinchle or to hoist a few at Dinty Moore's saloon. In addition to his celebrated addiction to corned beef and cabbage, and the low life generally, Jiggs also exhibited a healthy fondness for the fairer sex. Showgirls were his favorites (and favorites of the times), but in their absence any well-turned leg would turn Jiggs' head. Jiggs never tired of ogling women, and he indulged in his favorite sport in the office, on the street, even in the presence of his redoubtable Maggie. Once, while sitting on a panel to judge a beauty contest, Jiggs was asked to state his preference as to which contestant he liked best. He unflinchingly answered “All of them”—an accurate if rather succinct summation of his views on the subject.

With Bringing Up Father, which turned out to be a hit, McManus set the model for the comic-strip depiction of marriage as an institution bereft not only of any hint of sex but even of the slightest glimmer of affection. That The American public preferred the jaundiced view of married life expressed in Bringing Up Father to the rosy picture presented by the selfsame McManus in The Newlyweds is in itself a social comment of no small importance.

http://www.toonopedia.com/toots_ca.htm

There were exceptions to this bleak recital of marital woes (the loving couple of Toots and Casper and the warm conjugal relationship of the Kabbibles in Abie the Agent come to mind), but all in all the bedroom as seen in the funnies looked more like a battlezone than a love nest. In this context Clare Briggs' unsettling Mr. And Mrs. can be considered emblematic, with the mismatched couple Joe and Vi Green always at loggerheads, and their young son Roscoe forever uttering the same idiotic question after each of his parents' spats: “Papa love Mama?” (or “Mama love Papa?”). Even former sports like Mutt, once they got married, seemed to lose interest in all sex—at least with their wives.

And so it was with Barney Google (“with the goo-googly eyes”), who at the beginning of his adventures was married to a wife “three times his size” as Billy Rose's song put it. No sooner had he struck it rich on the racetrack, however, than Barney realized every American husband's unspoken dream: he ditched his overbearing spouse and set out in search of the “sweet mamma” of his lifelong yearnings ( any “sweet mamma” would do, as long as she was young, attractive, and willing).

If Barney Google embodies American comedy, Moon Mullins can be viewed (with some license) as American tragedy. The boardinghouse run by the scrawny, spinsterish Emma Schmaltz is inhabited by enough of life's failures to stock several road companies of Death of a Salesman, a grim (if hilarious) cross section of losers as long on color as they are short on funds and morals. These include the title character, a shady fast-talking hustler and unsuccessful promoter; his kid brother, Kayo, a miniature version of Moon, complete with derby hat and foul mouth; and the rundown English aristocrat Lord Plushbottom (“Plushie”), whom Emmy finally dragged to the altar in 1934; and Mamie, the elephantine cook and washer-woman, wife to Moon's ne'er-do-well Uncle Willie.

Riches and sex are the twin—and never fullfilled—ideals of this small band of outsiders and misfits. Under his rough veneer, writes Stephen Becker, “Moon himself is a romantic: he likes pretty girls and money, and his pursuit of both is reckless and devoted.” Plushbottom, when not putting on airs, is on the prowl for every shapely young lady in sight, in the great tradition of comic-strip husbands. Among these less than shining female lights the carnival dancer Little Egypt (Emmy's niece) twinkles bright, a creature of beauty and glamour; indeed, every man in the boardinghouse lusts after her. Their efforts are of course doomed: success unacheived and sex unobtained are two sides of the same debased coin. With the death of Moon's creator, Frank Willard in 1958, the strip unfortunately went downhill, and it is now only a pale imitation of its former self.

This chapter wouldn't be complete without some reference to the innumerable orphan strips that were such a staple of American comics in the first quarter of this century. The boy orphans, such as Bobby Thatcher and Phil Hardy, were all Horatio Alger types who dreamed of adventuring at sea or in faraway lands—no sissy stuff for them. Little Orphan Annie, missed being born a boy by a hair, and she has remained sexless throughout her long career as a waif.

Little Annie Rooney was a different case altogether. She displayed a Lolita-like sexuality as well as a coquettishness with men, who almost invariably Found her irresistible. Not so the women, however, and none was as rough on the angel as Mrs. Meany, the ugly, cruel head of the orphan asylum from which Annie was forced to flee again and again. In the course of her peregrinations she would often rely on the kindness of strangers (usually men) who offered her temporary refuge. It was this dual, ambiguous outlook that caused French critic Jean-Claude Romer to call Little Annie Rooney a cross between the Comtesse de Ségur (a cloying, sweet children's author) and the Marquis de Sade. As with so many other comic strips of the period, there was more to Annie Rooney than met the eye.

The early American comic strip is now nostalgically recalled as an embodiment of innocence, but this is a recent view. It was certainly not considered so innocent by legions of turn-of-the-century critics, who assailed it for, among other sins, bad taste and vulgarity. Had these self-proclaimed guardians of culture had gone through the trouble of actually reading the newspaper strips they were attacking (as the comic-book detractors later did with so much zeal), they might have added indignant prudery to their crusade. Let us be grateful that the early censors—as is often the case with censors everywhere—couldn't see the forest for the trees.

These are tame in comparison to the later chapters. The next ones will justify the Blogger disclaimer logging on to this page, and there will also be pages for those who don't speak English.

Uncle Scrooge #22 - Carl Barks art & cover

-

Uncle Scrooge #22

*Walt Disney's *Uncle Scrooge v1 #22, 1958 - Uncle Scrooge relaxes at a

remote cabin, only to be piqued by the legend of a gold river. Th...

4 hours ago

No comments:

Post a Comment