Here again are pictures and the text from an entire chapter of Sex in the Comics by Maurice Horn, a 1985 book about the history of the medium I've been posting here every Saturday. To see the previous installment go here which should have links to the one before it and so on.

As usual, I don't agree with all the language, particularly the use of the word “Oriental”, but that was still quite common in the 1980s, as was a patronizing view of women. I probably don't need to say it's NSFW since the wall before this post kind of implies that. So here it is then.

For reasons unknown, sex has always seemed freer in outer space or the further removes of time—at least in the comics. Perhaps the laws of society weaken along with the pull of gravity the further we move from Earth. At any rate, out there in the galaxies sexual fantasy goes hand in hand with science fantasy, in an unlikely meeting (or mating) of Einstein and Freud.

The first sequences in that granddaddy of all science-fiction strips Buck Rogers, give us a clue already. Here is Wilma Deering, the heroine, shuddering in her flimsy undies amid the paraphernalia of some space vessel, calling Buck for help. Things get hotter. Seems that the Mongol emperor who has taken over America in the twenty-fifth century has taken a liking to Wilma—he wants her for his favorite. Wilma escapes from his clutches, only to find Buck in the arms of an oversexed Oriental dancing girl who has taken a liking to him. And so forth.

The relationship between the two arch-villains, Killer Kane and Ardalka Valmar, was even more explicit. Like lovers in real life, they were always pawing or fighting each other when not conniving. Both also tried to steal their rivals' respective mates. When Ardala found Killer making passes at Wilma, or when Killer discovered Ardala throwing herself at Buck (and such interludes happened all the time), they would pitch earthshaking tantrums before going back to each other. It was all very refreshing.

The goings-on in Flash Gordon were just as uninhibited, only grimmer. There Ming, “emperor of the universe”, upon having the hero and his girlfriend Dale brought to him shortly after they land on the planet Mongo, flatly decrees, “The beauty of the female pleases me—she shall be my wife! The young man shall be slain as he does not fit the physical requirements of my army!' Flash vehemently protests, as might be expected under the circumstances, and Ming's beautiful daughter Aura comes to the rescue (seems she is crazy about him and wants him for her mate, as might be expected). Such are the exotic whims of Oriental despots and scheming sexpots the universe over.

If every female on the planet seemed to be after Flash, every male was panting for Dale. In addition she was always on the verge of being raped by libidinous hirelings, if not actually tasting the whip at the hands of jealous rivals or being tortured by sadistic jailkeepers. Dale could easily have passed for a younger sister of Sade's ill-starred Justine. It was great fun until the censors finally cracked down.

Brick Bradford, hero of a long-running strip of the same name, had no steady girlfriend, but more than made up for it bu constantly surrounding himself with a string of adoring beauties. He was an early example of an equal-opportunity employer: he collected women (and as rapidly dropped them) without regard to race, color, creed, or national origin. His conquests included, at one time or another, Inca princesses, Viking maidens, Indian high priestesses, African witches, female citizens of distant planets and even plain American girls. He treated them all with the same mix of familiarity and nonchalance bordering on disdain, and got away with it. Better yet, they always came back for more.

Only Connie spurned such facile amusements. Created by Frank Godwin in 1927, Connie went from socialite to social worker to space explorer during the seventeen-year run of her strip. Perhaps because she was a heroine in an unliberated age, she went through her paces with earnest dedication. Even her enemies allowed themselves no more than a leer in her presence, and her admirers kept a respectful distance. The impression, however, was that Connie could have gotten laid anytime she wanted, but that she simply wasn't interested. Racing through the solar system, fighting green monsters on alien planets and discovering new atomic elements gave her all the kicks she needed. Besides, all the males in the strip, even the villains, all looked like sissies.

And then there was Barbarella. When he created the strip in the early sixties for a French “girlie” magazine, Jean-Claude Forest never imagined he was blazing new trails. With all the adventure of a scantily clad (if clad at all) heroine, he thought he had just devised a comic strip for the amusement of his friends and the amusement of the male readers of the magazine. “What misadventures, what disappointments in love,” Forest asked in the very first panel in high mock-romantic fashion “have led this girl to wander alone through a solar system far removed from her own...?”

Barbarella, a beautiful girl with long blonde hair and golden skin, moves with aplomb through the thrills, dangers and horrors of the alien planet Lythion. There she encounters a variety of weird creatures and undergoes a number of bizarre sexual ordeals. Particularly noteworthy is the “excessive machine” in which Barbarella experiences a series of orgasms, each more violent than the last, which would have led to an ecstasy of death had she not been liberated in time. To die of pleasure indeed! And what about the sadistic whims of her lesbian lovers? First there is the Medusa, then Slupe, the one-eyed black queen of Sogo, whose life aims are stated in these words: “Look, Barbarella, look... There you see the entire scientific elite of Sogo! It's working for me and has only one goal in mind: to extend the frontiers of human pleasure... isn't that a noble purpose?” To which Barbarella replies, “Indeed it is!”

Fortunately, Barbarella knows how to use her charms, and she is ultimately saved from various hideous fates by a legion of male admirers: the handsome Prince Topal and the fearless Captain Sun and blind angel Pygar, not to mention Diktor the robot, who, by his own admission, can do everything—and with great care. Barbarella rewards all her saviorsin her own feminine way. Her very gallic élan and joie de vivre are far cries from Connie's puritanism.

In Barbarella, in his other creations in the science-fiction field (Hypocrite, Mysterieuse, etc.), Forest conjures up all kinds of female freaks, perhaps in an effort to counterbalance his too perfectly shaped heroines. There are sawed-up women, spotted women, inflatable women, three-breasted women, women with adjustable legs or detachable wombs. Among his most tantalizing creations are the “she-animals”, women with the heads of various animals. When a male member of a galactic exploration team has an assignation with one of them, she comes hooded but stark naked under her coat. In the midst of passionate sex the nonplussed explorer can't help wondering what kind of animal his partner is. He imagines her by turns as a vampire bat (from her sucking), a sow ( from her obscene grunts) or a bitch (from her mad yelpings at the climax). He (and we) will never know.

Barbarella gave rise to a host of imitations. Soon there were countless heroines roaming through space and time, ready to drop their clothes at the slightest provocation and indulge in every sexual fantasy. In Italy there was Uranella, a super(sexed) woman from outer space, followed by Gesebel, “an oversexed space heroine,” according to Italian comics historian Gianni Bono. Gesebel let no man dictate to her; she always took charge, always took the initiative in and out of the bed, and at one point she kept a male harem at her beck and call in her sumptuous residence.

Even the staid British got into the act. In 1969 the London Sun, under the enlightened readership of that great press tycoon Rupert Murdoch, brought out a new daily strip titled Scarth. Set two hundred years into the future, it starred a short-cropped blonde whose glorious changes of clothes did little to hide a glorious figure. Scarth was a liberated woman, at least as regarded her inhibitions (she didn't have any), but fell with monotonous regularity for any male she chanced to meet. Since she was supposed to be a troubleshooter for an intergalactic conglomerate, that covered a lot of territory. So did Scarth, though she seemed to prefer Earthmen.

Scarth's sexual partners, though many, mostly ran to human types, or reasonable facsimiles thereof. There were exceptions, such as a bearded hermaphrodite, antenna-equipped extraterrestrials, and a libidinous blob from outer space sprouting an alarming number of tentacles. Sex was depicted as an offhand interlude or part of Scarth's job or both. The strip benefited from the delicate and expressive draftsmanship of Spanish artist Luis Roca.

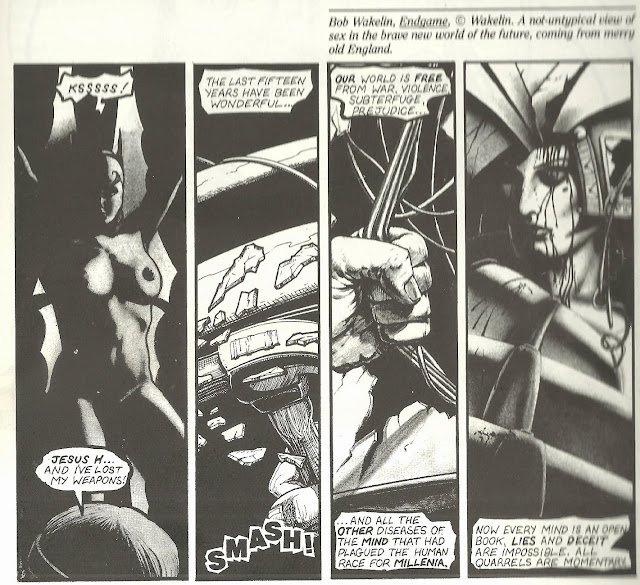

The last dozen years or so have witnessed an explosion of comics with strong science-fiction elements and overt sexual themes. Outer space seems to have become the last refuge of freewheeling sex, now that the much-touted sexual revolution of the sixties has somewhat ingloriously petered out here on Earth. The roster of cartoonist who have exploited (and that's often the right word) the field reads like an international Who's Who of comic art, and includes such luminaries as Berni Wrightson, Howard Chaykin, Phillippe Druillet, Juan Gimenez, Reed Crandall and countless others. Even Gray Morrow, in the recently revived Buck Rogers strip, tried to add spice to the relationship between the protagonists by having a sex-crazed Wilma slaver all over Buck (in the end it turned out to have been no more than unconscious fantasies triggered bt fumes emanating from the moon's craters).

Two artists, however, stand out in this crowded field, One is Moebius (Jean Giraud), who always injects a healthy dose of humor into even his most outlandish stories. The Horny Goof is a good example. The Goof, who lives on a little planet in a faraway galaxy, is afflicted with a permanent erection, and it causes him no end of trouble. As he himself explains at the beginning of his sad tale, “ I get up in the morning with a god-awful rod on me that won't go away. It isn't the hard-on season. That is autumn. So...I am ruined: pursued by the cops, shunned by former friends, can't get a good job. I have become a horny goof. That is the worst crime on Souldia du Cygne.” The Goof is rescued in time by the “space slut”, Great Dame Kowalsky, who gets wind of his condition and has him brought to her by her minions. War, famine, and pestilence rage, but the Goof and Kowalsky, oblivious to it all, achieve ecstasy in full 3-D video. (If the plof sounds like a demented cross between Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, it is probably intentional.)

Richard Corben, on the other hand, treats his obsessions with greater and greater seriousness as he grows older. In Rowlf (1969) Maryara, a splendidly beautiful maiden, is abducted by a ruthless horde of alien invaders whose weapons and superior organization allow them to overwhelm the girl's homeland. As she is about to become the plaything of the leering, drooling barbarians, Maryara is rescued by her dog Rowlf who has assumed half-human shape (and all-too-human emotions). Outwitting and outrunning the invading armies, they find a remote, unspoiled piece of land where they can live out their strange idyll. Humor and irony appear in this twist on the Beauty and the Beast motif, in the form of an old and decrepit sage who wryly comments on the action.

In his second version of Den, (1982-83—Corben is a compulsive re-worker of his own stories), the theme of man's innate bestiality and woman's embodiment of good (and, conversely, vessel of evil) is treated with a seemingly straight face. The hero is transported, by electronic means never fully explained, to a strange land called Neverwhere in which barbarism and technology go hand in hand (a recurrent leitmotif). There he finds his beloved, Kath, and after many trials retires to live a free (and naked) life of natural love and sex. The reverse image of Kath is represented by the black queen of Ne verwhere, who tries to seduce Den away from his beloved. This sounds like hokum (or perhaps a Wagner opera that didn't make it) but is saved by Corben's astonishing graphic mastery and the sweep of his compositions).

Corben's science fiction borders on heroic fantasy. In the paroxysmal motion of his images of sex, struggle, and death, he seems to validate Edward Rothe's prediction in Internationale Situationniste (September 1969) that “man will travel into space to make of the universe the playing field of the last revolt: that which will go against the limitations that nature imposes.”

Also no laundering…

-

The flip flops are very hard to remove… Photo courtesy of AH. Packaging

for signage.

2 hours ago

No comments:

Post a Comment